|

Click here for

index to all

Yellin stories for

The Japan Times

Click here

for another

story (1999) on

Kamoda Shoji

Click here for

an interview with Kamoda Shoji

(1980)

Click here for

Daruma article on

Kamoda Shoji

(2003)

Click here for

another Japan

Times Story

(Sept. 2005)

Yellin's gallery

sells pieces from

the kilns of Japan's

finest potters

|

|

|

KAMODA SHOJI

Soaring on the clay wings of inspiration

By ROBERT YELLIN

for the Japan Times, October 8, 2003

|

|

Jar 1974

Kamoda Shoji

|

|

|

1975

by Kamoda Shoji

|

|

|

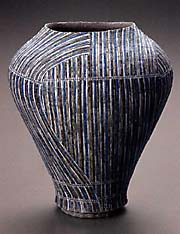

1979

Kamoda Shoji

|

|

|

1979

Kamoda Shoji

|

|

|

|

|

The mind and soul of a genius often seeks solace in cold, lonely places. In the intense stillness he works deep into the night like one possessed of a vision he knows will burn out with the coming rays of dawn.

This could be a description of the brilliant world of the late potter Kamoda Shoji (1933 - 1983), perhaps Japan's first superstar ceramic artist.

As if he knew his life would not be long, he worked at a feverish pace, never producing the same piece twice.

It was in June of 1969 that he packed up from the potting center of Mashiko and headed north to frosty Tono, Iwate Prefecture. It was there that he made the works that we find in the last part of a three-part exhibition titled "Clay Life Taking Wings, 1973-1980," now showing in Mashiko at the Mashiko Museum of Ceramic Art until Dec 7, 2003. (The first part of the exhibition, held in 1999, was reviewed in The Japan Times, Nov. 27, 1999.)

Kamoda likened his life to "walking into the north wind," even though the potter was said to be a warm-hearted and gentle soul. The harshness of the frigid wind of Iwate must have awoken him to the reality that nature is a double-edged sword. It certainly inspired his reflection that "man can accumulate simple things, but can never achieve something at once delicate and complicated. Only nature can do that."

It must not have been easy to feel this contradiction as he went about the art of creation. Yet, his life was full of contradictions, as we clearly see from his writings:

"Every day throughout the year, I am dissatisfied with my work" or "I have always performed unnatural things extremely aggressively. To make new things gives me a certain gratification, yet over time, the results just appear too unnatural, like how I had used a certain shade of red on a particular piece, yet to change isn't my goal in the first place."

Despite that last assertion, Kamoda was always changing his pottery style -- the decoration, glazing and form of his pieces were in constant flux. One reason for this was he was always dissatisfied with his creations. He only saw their negative qualities, and this magnified his own sense of worthlessness and guilt. The potter was so shy about this, he could never bear to see how audiences would react to his work; he never attended his exhibitions, only stopping by the day before the opening to make sure all was ready.

He would surely have been pleased, though, to see the reactions. Since Kamoda never sold through dealers, fans eager to acquire his clay creations had to line up at the gallery entrance hours ahead of the opening. Prices would often jump two or three times as the pots went out the door.

The works in the current exhibition are all made from the rough and stone-laden Tono clay. It is nearly impossible to throw works on a wheel using this clay, and most of the pieces were hand-built, by coils or slabs. This permitted the potter a freedom of form, and we find gorgeously odd polyhedral shapes right alongside traditional jars.

What is distinctively Kamoda, apart from the unusual forms, is the way he decorated his works. This involved a more than usually labor-intensive and time-consuming process that started with detailed sketches. It's interesting to note that unlike most other Japanese potters, whose sketches are often observational -- of birds, flowers and landscapes -- Kamoda's drawings, mostly geometrical and abstract patterns, are all from his mind.

His work is the antithesis of what many perceive Japanese ceramics to be -- load pots in a kiln and ask the kiln gods to bless them with accidental (but beautiful) kiln mutations. Kamoda knew well in advance how he wanted his works to look after firing. His is one of the keenest Japanese artistic senses ever expressed in clay: wavy, multicolored enamel lines; stained glasslike patchwork segments; coarse clay inlaid with delicate enamels; and gaunt, edgy, arabesque-looking designs.

The tall jar (1979) illustrated here is one of his masterpieces. The intriguing shape is quite complex: It starts out on a white rectangular base and almost immediately changes color, with a dark, glazed body that flares outward. Alternating bands of color sweep horizontally across the base and then suddenly shoot up diagonally across the front of the piece, ending in pulsating grandeur. Kamoda used this pattern not only on larger works but on sake vessels as well.

In the exhibition we find a new style each year, stopping at 1980, when Kamoda became too weak to work.

Even though Mashiko is a bit out of the way, it's well worth the trip to see this one-time only exhibition. I'd like to end with Kamoda's own searching words and let you ponder how the life of one man has so deeply touched the world of others:

"The advance of science has made the world smaller, yet even with the vast integration and collisions of various cultures, the Japanese are still Japanese. When I look within myself, it is plain that I see myself as a Japanese, and through these Japanese eyes I can see and understand where I stand in the world. I believe it is my mission to find, through my own personal world within me, and by my ceramic art, the inner roots of the Japanese. Just as I see an infinite universe outside of me, I see an infinite universe within me. Through a harmonious focus upon both universes, there lies the essence of my actions."

"Clay Life Taking Wings, 1973-1980" runs till Dec. 7 at the Mashiko Museum of Ceramic Art, Mashiko 3021, Tochigi Prefecture; tel. (0285) 72-7555. Admission 600 yen; closed Wednesday.

The Japan Times: Oct. 8, 2003

(C) All rights reserved

LEARN MORE ABOUT KAMODA SHOJI

|

|

|