|

Kamoda Shoji Revisited

Plus Translation of Interview with the Artist

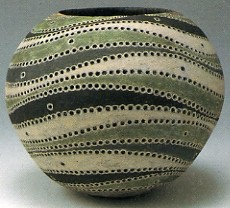

Tsubo by Kamoda Shoji, 1965

Photo courtesy of Honoho Geijutsu

Issue 18, 1989, Abe Publishing

Firstly, I'd like to thank all those who generously took the time, after reading the last column, to provide intriguing questions for discussion in future articles of JCN. I'm genuinely happy to receive such emails, as it gives me a good feel for what JCN readers are interested in; that makes me want to tackle a certain subject with much more energetic gusto than without an inkling of feedback. I promise to take on many of the questions posed in future articles, so please stay tuned. Again, thank you, and do please keep on writing.

We all have favorites. Ambivalence is not just dull but tragic, and those artists who embody and radiate emotion, whether it be love or hate, is a healthy and important ingredient to the melting pot that is the human condition (albeit apathy can be found to be an engrained and "respected" characteristic in some aspects of a given culture, such as the dearth of citizen participation in Japanese politics).

A few random 20th century loves of mine, apart from ceramics: Marcel Duchamp (of urinal fame), the Kinks (Waterloo Sunset is a sentimental favorite), Dazai Osamu (nobody quite portrayed drugged decadence and the loss of innocence quite as poetically, romantically, and pitifully as Dazai did in the 1940s), Federico Fellini films (such as the splendid 8 1/2).

And in regards to pottery, a name that surely stands out in my memory is Kamoda Shoji (1933-1983). Many of you have heard his name being tossed around in previous articles written by Robert-san, or may have caught his name in articles such as the Sugiura Yasuyoshi JCN interview.

Kamoda, like Tomimoto Kenkichi, Kaneshige Toyo and Yagi Kazuo before him, was one of the few potters to have "fired" a bold new ceramic scene single-handedly. Influential is an understatement, and mesmerizing were his works. Kamoda's work was the bell that woke the conservative Nihon Dento Kogeiten, or the Japan Traditional Art Crafts Exhibition, from its reactionary slumber, and allowed a new meaning to the term "functional." That meaning was this -- that the traditional could be synonymous with and representative of innovation. Functional vases could take on new shapes and designs that were like nothing that had come before. In other words, the ingenuity/creativity/techniques of a given artist could breath new life into traditional forms and pottery styles. Kamoda was the epitome of the notion that traditional crafts could be just as avant-garde as Yagi Kazuo and the Sodeisha (The Society of Running Mud), or the progressive ways of artists associated with the Nitten (Japan Fine Arts Exhibition). An artist that followed a similar path after Kamoda in the Nihon Dento Kogeiten was Kakurezaki Ryuichi, who offered a wildly revolutionary path for modern Bizen wares.

Kamoda was legendary at the potter's wheel, making razor-sharp edges to his pots while elegantly using the emerald ash-glaze that he learned from Tokoname great Ezaki Issei. However, Kamoda abandoned his minimal silhouettes for faceting and then hand-pinching, placing more and more emphasis on the decorative aspect of creation. And what was remarkable about Kamoda was that he, like his teacher/mentor Tomimoto Kenkichi, followed the Tomimoto doctrine of "to not make a pattern from a pattern." In other words, not only were the decorative patterns of Kamoda in a league of their own, they were motifs that were never before seen in Japanese pottery, and were never repeated after a debut. Kamoda was adept at churning out pattern after pattern in a perpetual artistic evolution. He devised symbols of expression that sprang from the rich well of his inner creativity, and his pouring of imagination and daring captured the hearts of fans and critics alike. Becoming a cult figure, Kamoda rose to the top of Japanese pottery; unfortunately, like many cult figures, he physically passed from this earth much too early, at the age of 49.

Kamoda's contributions and significance has been covered in great detail through Robert-san's vivid, lucid articles, and so I think it unnecessary to shuffle through the details once again within this column.

On the other hand, I've found in an old, obscure article in the ceramic quarterly Honoho Geijutsu #17 (1989, Abe Publishing), an extremely rare interview with Kamoda. I've taken the liberty of translating it, albeit in parts, within this column.

The artist disliked both interviews and the tape recording of his voice, and thus the tape of this interview was just one of two recorded interviews that remain today. It was an interview published posthumously, and would have gone unnoticed and forgotten if not for Honoho's interest in Kamoda six years after his premature death. I find this interview an important one, in that although many publications have been written on Kamoda, articles featuring an interview with Kamoda are extremely hard, if not impossible, to find. In particular, I enjoy the fact that Kamoda is both acute and blunt, without trying to please or appease, within the interview. You can see an artist's mind at play, and some of his comments, such as his discussion of Yagi Kazuo, are highly enlightening. I feel that the interview had previously gone unpublished due to the incoherency and inconsistency in the speech of Kamoda himself. Yet moreover, even after the article, the cult figure Kamoda remains just as enigmatic as ever, never loosening up or outpouring his emotions through easy deference to verbal exchanges. Rather, he was and remained the quintessential artist who expressed his inner angst with his art, not through words.

Please take a look, and see a glimpse of what went on in the artist's head, merely several months before he suddenly fell to illness.

Never Before Published Interview

Between Kamoda Shoji and Hasegawa Kimiyuki (Art Critic)

Honoho Geijutsu, Issue 17 (1989, Abe Publishing)

February 1980

(K for Kamoda, H for Hasegawa)

|

|

Work by

Kamoda Shoji

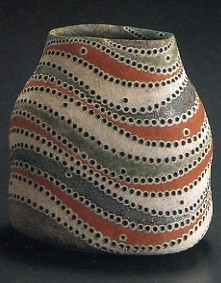

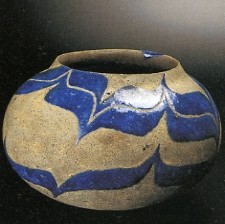

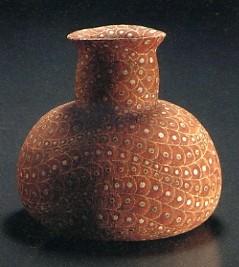

Tsubo by Kamoda Shoji, 1972

Tsubo by Kamoda Shoji, 1972

Tsubo by Kamoda Shoji, 1973

Tsubo by Kamoda Shoji, 1976

Tsubo by Kamoda Shoji, 1971

Photos courtesy

of Honoho Geijutsu

Issue 17, 1989, Abe Publishing

|

|

|

|

On the Transformation

of His Works

H: Kamoda-san, you had a period where your works were called "Sueki-esque" by many people. But then, at one point, your works turn to something similar to the style you have today. Does the change in your works come quite naturally from within you, or are they quite calculated, so that you can reach your fullest potential?

K: In regards to change, it might be that I'm easily swayed by impulse and whims. When I change a method, it's because I want to feel something new and fresh. In other words, I don't like complacency. But honestly, I would like to keep working in the same way, while changing not my methods but the heart and spirit with which I work with.

H: If the goal is to recreate old styles, it is often important to reject change. But if you do not take such a stance, than I imagine it to be incredibly difficult to constantly change while retaining a sense of freshness.

K: I think all my freshness has faded away (laughing). (A moment of silence)...I think I've always done unnatural things rather aggressively, and this is probably a reason for my rapid changing. That's why I always view my works as being unnatural, and I hate the works that I've made. But at the same time, I guess it's a rather rotten feeling to be too natural and perfect.

H: You just said "unnatural" and that you "hate your own works." Is this in regards to aesthetics?

K: No. I make what I want to make. But when I look at the results.

H: I think that as an artist whose profession is to constantly "create," it must be the end of creativity when you think you've done it all.

K: Picasso constantly changed as well.

H: With Picasso, he constantly absorbed so many different aspects, and then made them his own and used this as a method of change. But aside from Picasso, an artist who is so talented and adept at so many different things is, in many ways, a tragic figure, to put it coldly. For you, Kamoda-san, pottery fans and critics alike inflated so much anticipation upon you. When and how did you cut such pressure off, and just how much did you pay up to their anticipation: isn't that a difficult thing to do?

K: I've always felt antipathy towards being labeled "always changing." Besides, my goal is not about change itself.

H: I think it's different, the way artists view it, and the way critics and fans view it. In any event, it's probably impossible to constantly change in order to please people. True originality doesn't work like that, and for people who've never made anything in their lives, it must be a difficult thing to understand.

K: I don't think I've evolved or improved. I'm just living life, and my work comes from living. There's nothing really more to it.

On Form and Decoration

H: Yakimono (pottery) has two elements: form and decoration. As an artist, you've pursued the limits of form, while you've also pursued a multitude of decorative patterns. What is the relationship between form and decoration to you, or to put it differently, is there one that comes before the other?

K: One does not come before the other.

H: But when you make pottery, don't you start with a certain image before you work?

K: Yes, that is true.

H: If that is so, do you start with an image of glazes and colors, or proceed with a certain concept of form?

K: In my case, I intend to have glazes and forms more or less decided from the very beginning. I imagine a basic framework, and depending on how I'm feeling at the time, I start filling in the gaps.

H: You do not make works that only exist as objet d'art. Thus, you do not pursue an avant-garde testing of form, but rather, keep yourself in a relatively traditional format in regards to form. So I suppose your works, while keeping within the realm of tradition, tries to surpass "traditional" form.

K: I do not make objet, for it is not my personality.

On the Potter's Wheel and Hand Pinching

H: Please tell me about how you form a work.

K: When I was a student at the Kyoto City University of Art, the first year was spent on hand pinching. What I felt at the time was that I instilled feelings in each and every work that was shaped in my hands. But after I graduated, I think my work has become crude. I was making a hundred plates a day on the potter's wheel, for when I first arrived in Mashiko, I felt as if I had to try very hard to succeed. When your livelihood is at stake, that early feeling of instilling feeling into each work is very hard to retain and maintain. Even with my early work that won prizes at the Nihon Dento Kogeiten, I never had the feeling that I was actually "making" a work. The only emotion I had at the time was that I wanted to win a prize, for I needed to make a living. Around 1960, I stopped using the potter's wheel all together. By using my hands, I received a sense of comfort, a feeling that I was actually making something, rather than producing something. I felt as if I had returned to my college days.

H: Are you saying that you were able to have greater freedom in form?

K: No. I think that even if you hand-pinch, there will remain limitations to how you may form. If you try to intentionally push for more freedom, the more unstable and uncertain you become, and you lose the feeling of creating something.

H: But don't you think that your method of hand pinching has strongly influenced the young potters of Mashiko?

K: It's true that there are many young potters in Mashiko who make pottery through hand pinching, and there are some who say that they will never use the potter's wheel. It's true that hand pinching is enjoyable. But this is because you can make a space within certainty. The wheel is like casting. You get a lump that is made by pouring.

H: There are many people who think that you cannot make pottery without the wheel.

K: The potter's wheel is not a difficult tool to use. If you have a month with clay and train yourself, you can master it.

H: It seems that if you learn the wheel at an early age, you can basically master it quite easily. Tomimoto Sokichi (movie director, and son of Living National Treasure Tomimoto Kenkichi), said that he used to copycat his father at the wheel when he was small. In regards to spinning, Sokichi says he is basically unbeatable!

K: Daddy Tomimoto learned the wheel at a much older age; perhaps that's why he wasn't very good at the wheel (while laughing). Tomimoto-san was a strong-willed man, and if he saw you spinning with ease with the intention of mocking him, he would poke fun. "Wow, just like the bicycle, once you learn, you can't stop, can you?" Tomimoto would tease. What I admired about Tomimoto-san was that he often had craftsmen spin his works, but sometimes, he would spin the works on his own. But when he made them on his own, he would make works with great strength. It's not about who's good or who's bad on the wheel. Sensei's work had vitality. For those unaccustomed to pottery, the wheel appears as if it is something special or magical. It's really not like that at all.

On Moving to Tohno

H: Did you move to Tohno, Iwate Prefecture, with the hope of achieving something different?

K: Yes. Tohno is a wonderful place. It is pure and fresh. It is like the Mashiko I knew when I was starting out. It is unlike that of Kyoto pottery, which is so cramped. I don't like it.

H: Will you continue to work in Tohno?

K: Yes.

H: That would mean you have three locales for creation: Tokyo, Mashiko, and Tohno. Are you considering adding to the list?

K: I do not intend to travel for holidays, but I would like to eventually live in many different places.

H: Does a change in clay change your style of pottery?

K: Yes, it is true that a change in clay will change one's pottery. (Pause) Some people think I moved up north to Tohno because the clay was good. This isn't true. I basically feel that if the clay of Tohno could be fired above bisque-firing temperatures, than the clay would be suitable for pottery.

H: Do you mix your clay?

K: If the Tohno clay that I'm using is of poor quality, I sometimes mix it with Mashiko clay. People who buy my works buy them so that they could use them, and because of this, I intentionally glaze the insides of my works so that they could be used more easily. At my workshop in Tokyo, I try to avoid Tohno clay. I must admit that it is difficult to obtain good clay. And when you have good clay between your fingertips, your feelings and emotions change. Tohno clay, regardless of its quality, matches the terrain. I find that the atmosphere of a certain land and its clay are closely related. The same goes for Tohno.

On Yagi Kazuo

H: Although you were raised in Kyoto, you deliberately chose to work in Mashiko, which is in the Kanto region. Is this because in Mashiko, each potter could have their own kiln? Or was it the clay?

K: It's both. When I was a student in Kyoto, we had to share kilns. A potter having his own kiln was unthinkable. And back then, a potter was a special profession. But in Mashiko, everyone was working in a relaxed and laid back manner, and that attracted me greatly. The land surrounding Mashiko was rich and bountiful, and I felt that the clay of Mashiko was just as rich and charming. It was worlds apart from the processed, dull Shigaraki clay that we used in Kyoto. The clay of Mashiko felt much more alive.

Yagi Kazuo knew a great deal about materials, and so he effectively utilized glazes to bring out the best in a certain material. His forms weren't half-baked, either, and you could tell that he was truly a "potter," not a self-proclaimed "artist." But in my eyes, although there were many things to admire in Yagi's work, there were many aspects that I thought were petty. It was the embodiment of the Kansai person's desire to try new things. It can be, in many ways, superficial, and this lack of depth blatantly comes out in a chawan (teabowl) or guinomi (sake cup). Such is not only obnoxious, but it is a flippant attribute that calls for scorn.

H: But Yagi-san, for example in his work in Kokuto (black ceramics) in his later years, can be considered a highly original and revolutionary artist, no?

K: Yagi-san does not like my work. I think he finds it vulgar and grotesque. I first met Yagi-san two years ago, and he went out of his way to criticize me in person. But I understand that he probably heard many rumors about me from various circles when I still lived in Kyoto, and the fact that I rejected Kyoto didn't seem to go down well.

H: Since both of your were potters at the cutting edge, both of you were sensitive to one another's work, for better or for worse.

K: I thought Yagi-san to be a very honest and innocent man. After meeting him, I would have students of Yagi-san come to study with me in Mashiko. Yagi-san would tell them not to go to me, as it would make it harder for them to succeed. I think Yagi-san thought I was living like a holy hermit.

From Painting to Pottery (Kamoda's College Days)

H: I hear you first pursued a career as a painter.

K: That was in high school. I wanted to continue painting. And to paint, I thought I had to go to Tokyo. But I was a coward, I had no money, and if I remained in Kyoto I could go to school while living at home. But in Kyoto, my will to paint faded rather quickly, and I jumped on the first thing that looked interesting. That was pottery. I'm grateful that I met pottery at that time, and I'm grateful to have been able to meet someone like Tomimoto-sensei.

H: Why did ceramics appeal to you at the time?

K: When I was a child, I thought of pottery as very old-fashioned, for old people. Kyoto had an image of Japanese painting. But when I was growing up, the amount of people who took interest in Japanese painting was very few. Even my teacher in high school, who was supposed to be a teacher of Kyoto-style Japanese painting, would not teach us Japanese painting. But I think the way he taught was wonderful. Since he didn't force Japanese painting on us, we were free to explore, and he showed us many books and pictures on Picasso, for example. In Japanese painting, he did teach us Koetsu, Sotatsu, Korin. My teacher was a slave to gambling, betting on cycling and derby racing. But he was a good man. My paintings were horrible. I couldn't paint a concrete object. It all turned out abstract.

H: So, your deference towards abstract motifs on your pottery stemmed from your days in high school, no?

K: Yes. In Kyoto, I was always good with patterns.

H: Do you still have works that you've made in high school?

K: Just one, which is at home. It is like what I do now. Nothing has changed.

H: Do you have any favorite artists?

K: There are types of paintings I enjoy. Modigliani, for example. For sculpture, I enjoy Brancusi. You might think me distasteful, but I also enjoy the Japanese painters Kishida Ryusei and Sekine Shoji. They feel good. But I think Picasso was a painter who lived the strongest, just like a grand old tree that naturally withers and dies.

End of Interview

Afterword by Hasegawa Kimiyuki

This conversation was recorded in Showa 55 (1980), when I traveled throughout Japan and interviewed many artists so that I could write a philosophy of art. One of those artists that I interviewed was Kamoda Shoji. I visited him in his home in Mashiko, and in place of a memo, I recorded the conversation that you have just read.

Kamoda fell ill the summer after my interview, and could hardly pursue his art. When I had interviewed him in February, he was very well, and during lunchtime, he would drive me to the one restaurant in town and talk of many things to me.

And later, he even agreed to let me into his workshop in Tokyo, and generously allowed us to photograph how he worked, using a tatara (clay board) and making a cylindrical shape. There was no premonition or indication of illness at the time, but in just three years after this interview, Kamoda passed away -something completely unthinkable.

Now, as I listen to his voice on my tape recorder, I think again that he was an artist that had an amazing potential for even greater art. To have passed at the young age of 49 -to Kamoda, I pay my sincere and utmost respect, as well as a heartfelt regret.

Hasegawa Kimiyuki

Kamoda Shoji

- 1933 Born in Osaka.

- 1952 Enrolls in Kyoto City University of Art, being taught by LNT's Tomimoto Kenkichi and Kondo Yuzo.

- 1955 Wins his first award at the age of 22 at the Shinshokai Exhibition.

- 1959 Becomes independent.

- 1960 Marries wife Masako, hold his first individual exhibition.

- 1961 Wins first prize at the Nihon Dento Kogeiten, winning consecutively ever since.

- 1962 Builds anagama (underground single-chamber kiln).

- 1964 Nominated as a full time member of the Dento Kogeiten.

- 1966 Receives Japan Ceramic Society (JCS) Prize, and his work for the Dento Kogeiten is purchased by the Agency for Cultural Affairs, a branch of the Ministry of Education.

- 1967 Begins splurge of individual exhibitions, never selling through dealers.

- 1981 Diagnosed as having leukemia.

- 1983 Passes away at age 49.

End story and translation by Aoyama Wahei

written for yakimono.net & e-yakimono.net

INDEX TO

ALL STORIES

by Aoyama Wahei

|