|

Sake Vessels Series (July 2003)

First published in Honoho Geijutsu, #73, Feb. 2003

"Talking About Sake, Getting Drunk on Ceramics"

Used with permission of Abe Publishing

Translated by Keiko Nishi

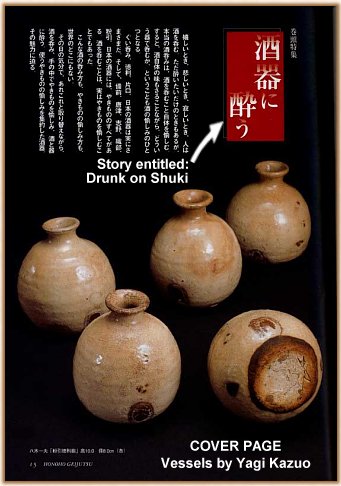

Cover Page

Honoho Geijutsu, Issue 73, Feb. 2003

Shuki vessels (sake cups called guinomi, flasks called tokkuri, spouted-pouring vessels called katakuchi, and other forms) are the first things usually acquired by pottery fans (yakimono enthusiasts). Pouring sake from a tokkuri and caressing the flask with one's hands, and then sipping sake from a guinomi and playing with the cup in one's hands when drinking alone, these bring a peculiar bliss to yakimono lovers. From that point on, some become possessed by chawan (tea bowls) or tsubo (jars).

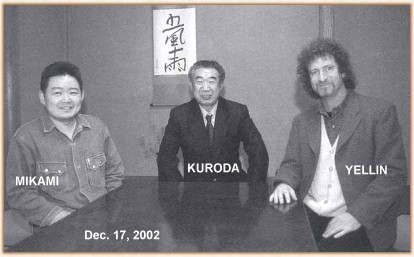

For pottery lovers, Shuki usually represent their first introduction to the world of yakimono, and for many it can also remain their ultimate destination. Yakimono is always around us, and we use it in our everyday life. Shuki only become better with use. Below is a discussion among three yakimono lovers who will drink and talk endlessly about the charm and magic of shuki. They are:

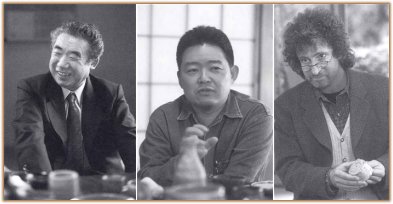

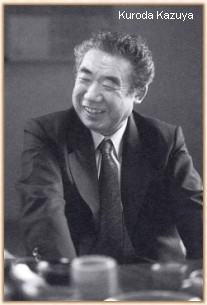

- Kuroda Kazuya (Japanese Ceramics Society Board of Directors (Nihon Toji Kyokai), Chief editor of "Tosetsu," and Ginza Kuroda Toen, President)

- Mikami Ryo (Ceramic Artist)

- Robert Yellin (Ceramic Journalist, e-y Net Corporation, Director)

- Moderator: Matsuyama Tatsuo (Chief editor of Honoho Geijutsu)

(L) Kuroda Kazuya (M) Mikami Ryo (R) Robert Yellin

GUINOMI ARE LIKE MINIATURE CHAWAN

Moderator (M): Since this is a roundtable talk about shuki, let's relax and enjoy. It's only daytime, but talking about shuki without really using it is no fun! So, I would like all of you to enjoy sake with your favorite shuki that you brought and to share your knowledge about sake and yakimono. First, I would like to ask Kuroda-san, who is the senior member among today's speakers, to tell us how guinomi came into common use.

Kuroda (KK): Drinking vessels for sake were generally called "sakazuki" -- the word guinomi was seldom used. At some point, restaurants and bars in the Kansai region (Western Japan) began serving aperitifs in deep drinking vessels, usually glass cups, and these vessels were called guinomi. This custom of serving aperitifs (like plum wine) in glass vessels has remained, but such vessels are no longer called guinomi.

M: Sakazuki reminds us of omiki (libation), doesn't it? Sake is an inevitable accompaniment to auspicious occasions and ritual ceremonies. Then, who started calling it guinomi?

Yellin (RY): That was Kitaoji Rosanjin, wasn't it?

KK: Well, I am not so sure about that. It wasn't that long ago when the word "guinomi" was written on hakogaki (the calligraphy on a box stating its style, form and maker). Rosanjin wrote "sakazuki" in the beginning of his career. Yet, I can say that Rosanjin was the first person that made guinomi as it is now.

M: Could it be one of the reasons that people began drinking alone was because there became fewer occasions to have drinks with other people at parties than before?

KK: I have heard that there were drinking counters at restaurants-bars in the Kansai area, but not in the Kanto area (Eastern Japan). I assume that people became used to drinking at a counter, and the custom was introduced to the Kanto area. Because of that, sake and food changed so a customer was able to drink alone, and for a cook to pour sake for his customers. And, following necessity, the size of sakazuki became bigger.

RY: Indeed, old pieces are smaller.

Mikami Ryo (MR): Sakazuki makes me feel more like drinking with someone rather than alone.

M: In the past, Geisha serving clients used sakazuki at parties. By the way, when did guinomi become expensive, like 10,000 or 20,000 yen?

KK: It must have begun when yakimono became a fad. But, their prices are not dependent on size. It takes the same labor and time between making one chawan and one guinomi.

RY: Guinomi is often called a miniature chawan. Every part of it, like the kodai (the foot), kuchizukuri (the lip), and koshi (the hips), is difficult to make.

M: Excuse me for dwelling on this, but the price of guinomi is not so different from tokkuri, is it?

KK: At first, tokkuri was about twice as expensive as guinomi. And, guinomi was one tenth of chawan. Currently, it varies depending on the piece.

RY: People from other countries usually are surprised to find that yunomi (a green tea cup) are cheaper than guinomi, although yunomi is twice as big as guinomi.

M: Is that because yunomi is usually mass-produced?

KK: Yunomi is essentially made about the same size. But the size of guinomi varies. That makes it interesting.

MR: Yes, that's right. Yunomi is thrown on a rokuro (a wheel) as a set. The heart and soul put in yunomi and guinomi are different. From the standpoint of an artist, pieces thrown on rokuro and ones made with hands (tebineri) turn out differently. When I throw a piece, I follow the character and peculiarity of clay, and spontaneity is important. On the other hand, because a piece made by tebineri does not have to match with other pieces, I can dig out a shape from a block of clay, and also there are many different ways of forming, like applying a himozukuri technique (coil-built) or using rokuro at the same time. In other words, it is easier to show the artist's character in a tebineri piece. We could also show our individuality in the lip and foot.

KK: Even ceramic artists who don't drink make shuki these days.

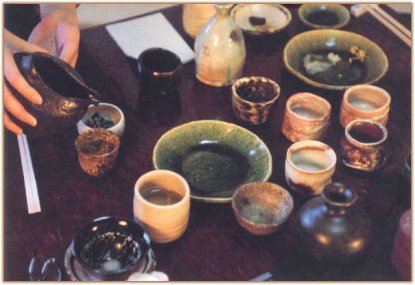

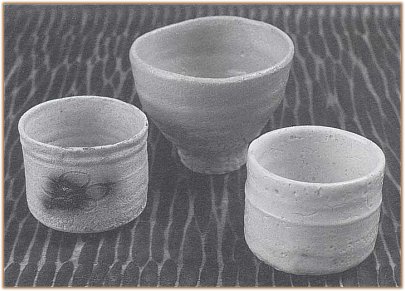

Shuki by various artists (brought by the speakers)

From right to left:

OKUISO Eiroku "Shino Guinomi

TSUJI Seimei "Shigaraki Guinomi"

EZAKI Issei "Haiyu (Ash Glaze) Guinomi"

OKUISO Taigaku "Shino Guinomi"

From the collection of Robert Yellin

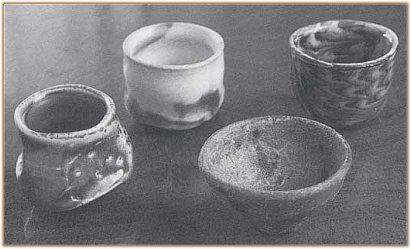

From right to left:

FURUTANI Michio, "Iga Tokkuri"

FURUTANI Michio, "Shigaraki Guinomi"

FURUTANI Michio, "Shigaraki Guinomi"

From the collection of Robert Yellin

From right to left:

MIKAMI Ryo, "Kuroyu Katakuchi"

MIKAMI Ryo, "Ruriyu Guinomi"

MIKAMI Ryo, "Katsuyu Tokkuri"

MIKAMI Ryo, "Haiyu Kohiki Guinomi"

MIKAMI Ryo, "Yakishime Hari Zogan Tokkuri"

MIKAMI Ryo, "Kuroyu Hari Zogan Guinomi"

KURODA Kazuya - Born Tokyo 1931

Graduated Keio University 1953, Degree in Law

He has published many books, including:

"Yakimono Fudoki," "Zukan Nihon Yakimono Meguri,"

"Zukan Kitaoji Rosanjin-no-Shokki,"

and "Chawan Kamabetsu Meikan"

RY: When I buy a guinomi I can figure out if the artist drinks or not, in most cases. I can tell by how it feels in my hands and on my lips.

KK: The artist Kusube Yaichi never drank alcohol. In his later life, I asked him to make a guinomi. His guinomi turned out to be similar to "O-choko" (small cup). On the contrary, Koyama Fujio loved sake. He often said that sake is not to be drunk, but to wet his lips.

RY: In the case of a thin-lipped guinomi, the tip of the tongue touches sake first. Therefore, you can taste the sweetness of sake. When sake goes deep in the mouth, the tongue captures bitterness. In short, the same sake tastes differently depending on the guinomi.

MR: It changes tremendously. Sake tastes differently with a porcelain piece as well.

KK: I heard from Hattori Yukio-san (a well-known culinary teacher) that taste feels most strongly at the back of the tongue. That is why when one drinks sake one should quickly drain the cup. I mean enjoying the taste of sake with one's throat. I believe guinomi is a vessel to enjoy sake like that.

TOKKURI ORIGINATES TOKKURI ORIGINATES

FROM TEA CEREMONY

TERM

M: It is hard to tell just by looking, but tokkuri made by contemporary ceramic artists can probably hold two or three "go" (1 go = 0.18 liters). They are different from the ones used at izakaya (a Japanese-style tavern).

KK: Bigger ones are called "o-azuke tokkuri," and the term came from the kaiseki meal during the Japanese tea ceremony. The tokkuri is for the tea master to leave to the guests when he is away from the tearoom, so they are relatively big. The ones used at izakaya are called "o-choshi," and they contain one go of sake. But, upper-grade restaurants (ryori-ya) use tokkuri that can contain only eight shaku (1 shaku = 0.018 liters). The two shaku will be the restaurant's profit.

M: I see. That's why o-choshi has to be mass-produced in the same size.

KK: Additionally, there used to be tokkuri called "binbo (poor-man's) tokkuri" used by liquor stores for them to sell smaller amounts of sake. Meishu (fine sake) or the name of a store was written in big letters on such tokkuri.

RY: You are talking about Takada tokkuri from Mino.

KK: Yellin-san. You know so well.

M: Yellin-san, you know more about sake and yakimono than Japanese. When did you become interested in sake?

RY: Right after I came to Japan (in 1984). While working as an English teacher, I looked at yakimono whenever I had time. Before coming to Japan, sake was just hot alcohol to me. There was no cold sake or warm sake available.

M: Was that in a Japanese restaurant in America?

RY: Yes. It was too hot to have any sense of the taste. That was probably cheap sake. But now, sake is quite fashionable in America.

MR: If Americans know about guinomi too, that would be even better.

RY: That's part of my current job. Now, about only one out of ten sake drinkers I would say are interested in vessels. The price of shuki is not cheap, so it depends whether or not they can understand that. My collection began with a 700-yen guinomi by the way.

KK: Lately people began making sake in America. Nigata prefecture and California state are working on the project together.

RY: Even sake made by smaller kura (sake breweries) can be purchased on the Internet (www.esake.com). Good sake made by a kura with good craftsmen won't lose to any wine (in terms of complexity and character). The taste of such sake is quite deep.

M: I heard that some upper-class French restaurants serve sake, calling it SAKE (spelled in capital letters, not kanji).

RY: Sommeliers sometimes come to Japan to study sake. However, just drinking sake is not good enough. One has to drink it using guinomi and tokkuri; the ambiance is also important.

SAKE LOVERS MAKE MASTERLY PIECES

M: Among great pottery masters, who was it that loved sake so much he made shuki in vast numbers?

KK: I think that would be Koyama Fujio.

RY: He made many kinds of shuki, like Rosanjin did. Koyama made Kohiki, Nanban, Bizen, Shigaraki, white porcelain, and so on.

KK: He was physically big and tough. Once he sat in front of the rokuro (wheel), he threw about 100 pieces in the blink of an eye.

M: For a ceramic artist, one can't make good shuki without thinking about what kind of guinomi and tokkuri one wants to drink from. What do you think of that, Mikami-san?

MR: Because I enjoy drinking, and because I like to use shuki myself, I make a great effort making shuki. Drinking sake makes me want other kinds of yakimono as well; that's how it is for me.

M: Rather than making something people would like to buy?

MR: Making what I want to use. That's the bottom line. I began making ceramics when I thought it would be nice to drink sake from guinomi I made. I was deeply moved when I made guinomi for the first time.

RY: My impression of Mikami-san's work is that it's changed a lot.

MR: Well, little by little. My world made with clay, glaze, and firing has changed, not only how my works look.

M: It feels to me that the older you have gotten, the more fixed your style has become.

MR: It's not fixed yet, though. I think it's good that young artists should have many interests and explore them. Experiencing life has something to do with sake in that shuki is a way of life, or a philosophy of the person. That is the bewitchery of shuki. From my point of view as an artist, that is interesting. It's said that chawan is the same way.

KK: Chawan has rules, but shuki doesn't.

MR: That's right. That's why I can make shuki in whatever way I like. (laughs) It's only to a certain extent, though.

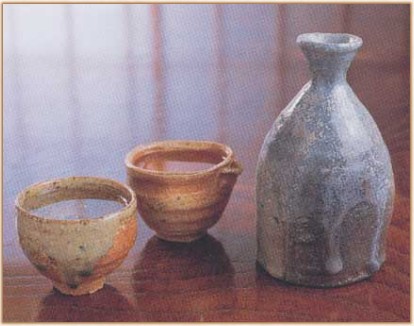

From right to left:

Bizen Tokkuri and Bizen Guinomi

From right to left:

Sometsuke-hai, Kohiki Tokkuri, and Haiyu Guinomi

From right to left:

Hakuji Tokkuri and Hakuji Guinomi

Hakuji means "white porcelain"

SHUKI CHANGES WITH THE TIMES

M: What do you pay the most attention to when you make shuki?

MR: First, there is material, so I look at clay and the firing. It's not totally up to what I want to do with them. There is a limitation as to what the clay can express. So I try to bring the expression out of the clay. Of course, technique plays an important part, as I said earlier. But, shuki has its own expression, like making people strongly aware of drinking sake when they only look at shuki. I have clear ideas about clay and firing, as well as the taste of sake, of being drunk, and of the drinking activity itself. There is a history of this in the clay and firing and this is one reason I am fond of yakimono. I don't want to miss those ideas and feelings.

M: I heard that you helped Asano Yo in his work since your days at Tokyo University of Fine Arts. Asano was a master chef and was well known for his food vessels, and so you know much about cooking too. Yet, you seem to have a stronger feeling toward shuki than toward tableware.

MR: Guinomi that is. The pleasure of using guinomi is more profound, I think. Tableware is taken off of the table as soon as dinner is over. Food is the main thing rather than tableware. Those pieces are there to make food look better. But, in terms of guinomi, both guinomi and sake play equal roles.

M: Do you usually drink alone?

MR: Yes. Most of the time.

RY: So do I.

M: It's a pleasure to have a guinomi, a tokkuri, and some shiokara (salted squid entrails) on a tray and enjoy sake alone, isn't it?

RY: Oh yes. I enjoy that very much. I enjoy the feeling of the artist I get from the shuki. I am by myself, but I am not alone. (laughs)

M: Nowadays katakuchi (spouted-pouring vessels) are used often as shuki. Sometimes cold sake is served in katakuchi at izakaya. When did katakuchi appear?

RY: It's been around since earthenware vessels. We also find lacquer katakuchi.

Shigaraki Katakuchi by Furutani Michio

This photo was not part of the original article.

It has been added to this web page for the convenience of viewers.

MR: Katakuchi was originally a tool to measure sake and vinegar. I think it wasn't until recently that people began using katakuchi at dinner. It fits our contemporary lifestyles to enjoy katakuchi like that.

RY: It's easy to pour sake into a katakuchi from a large issho bottle (1.8 liter bottle). That makes it easy to use when drinking with a lot of people.

MR: I began creating katakuchi seriously when sake breweries started selling cold sake, like Ginjo-shu. There had been no flavorful sake like wine before that. When that kind of sake is poured into katakuchi, the flavor spreads. Sake itself has changed.

M: Women even drink sake nowadays.

BEAUTY OF JAPANESE CERAMICS COMES FROM THE HEART

M: Yellin-san, you are more Japanese than Japanese. What made you become interested in yakimono?

RY: First, I was interested in the differences of food cultures. I wondered why there are so many different vessels in Japan. Having the special opportunity of being in Japan, I got interested in sake. So, I went to some izakaya to do some tasting. A basket full of guinomi was put in front of me and I had to choose one. That was a lot of fun.

M: As time went on, you started to see the differences between styles, and you got deeper involved. What interested you the most among at first?

RY: Yakishime, it was. In the beginning, I was interested in where the sense of beauty of yakishime comes from. Ceramics from America and Europe look beautiful outside. I felt the beauty of the Japanese ceramics comes from the heart.

M: Certainly, tableware is usually porcelain, and they are usually sets. On the other hand, each Japanese ceramic work is different.

RY: Ishihaze (stone bursts), Yu-no-chijire (glaze shrinkage), Kama-kizu (kiln cracks), and such -- why are they considered beautiful? It's quite interesting. There is a poem in it. A poem you can hold in your hands. One day a friend of mine told me that a piece with kama-kizu, or a piece that was "swollen" a bit, was a fine piece. I didn't get what he was talking about back then while we were drinking together. But, such yakimono actually matches my spirit now. (See various Japanese glazes and keshiki).

M: Generally, the Western way of thinking is logical and rational. But recently more people are interested in "the natural beauty" of Japanese yakimono. For example, I hear that a lot of ceramic artists fire yakishime wares in wood-fired kilns in America.

RY: That's right. Sake is in fashion and there's an anagama (single-chamber kiln) boom as well.

M: Why have American ceramic artists -- who had been focusing on sculptural shapes and other designs -- now begun paying attention to clay and firing? Is it because they now have come to understand the sense of beauty in Japanese yakimono?

RY: Well, I am not sure about that because the (food) culture is so different. Making food vessels and shuki requires a different philosophy from making sculptures and contemporary ceramic art. There are many ceramic artists from overseas coming to Japan to study pottery making, though. (And I'm sure many of them have come to understand that beauty)

M: So, it is more like an admiration than an understanding of its sense of beauty?

RY: Yes. There is probably the admiration of knowing -- like Japanese potters -- that you can control something only to a certain point. The rest is up to the clay and the kiln.

KK: Some Japanese ceramic artists who were invited to America to create ceramic art there told me there is no better place to find so many different kinds of clay, good quality clay.

RY: Red clay used by ceramic artists active in NY is very similar to Bizen clay.

M: Basically if the clay has a sticky nature, can it be used for pottery making?

MR: It's said that, basically, there is no clay that cannot be used for making yakimono. It depends on how it is used. Some clay can be used when the firing temperature is changed.

KK: In Bizen, clay is left for a while to have bacteria grow out of the clay. So, the historical disposition of clay is something.

M: Do recent artists go look for clay?

KK: There are some artists who use clay and glazes sent from their clients upon the clients' requests.

MR: That's right. But, as an artist, it's more than the kind of clay you use, it's also where you build your kiln. During the firing, the climate and place affect the work. It's not interesting if you're not conscious about it.

M: Both clay and firing come from nature. Natural things combined with natural elements make complicated objects. Japanese yakimono has such profound feelings.

SUZUKI Osamu

Shino Tokkuri and Shino Guinomi

Born in Hokkaido, 1959

Graduate, Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music

Master in Ceramics, 1986

. After teaching as a seasonal professor at

Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music,

Mikami-san trained under the late Asano Yo.

Currently lives in Minami-Ashigara, Kanagawa Prefecture.

Full member of Nihon Kogei-kai. Has held many solo exhibitions.

Robert Yellin

Born New Jersey (USA), 1960

Moved to Japan in 1984. Lives in Numazu, Shizuoka.

Taught English at Aoyama Gakuin University, Nihon University, etc.

Since 2000, has managed various websites that

introduce Japanese ceramic art to overseas audiences.

www.japanesepottery.com

www.e-yakimono.net

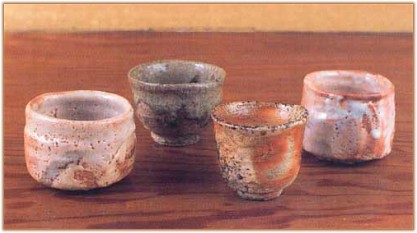

From right to left:

Pieces by HARA Kenji

Shino Guinomi, Shino Guinomi, Ki-Seto Guinomi

WHAT TO LOOK FOR, WHAT TO DRINK

M: Now, could you please show us the shuki you brought along today? After saying that, I know we have been using most of them already. (laughs) First, Yellin-san, which one do you have the most reminiscences with?

RY: I acquired these tokkuri and guinomi from Furutani Michio when I visited him with former English students of mine (see fifth photo from top of page). He passed away much too early two years ago. He was such a fine man and his work is refined. I also find that the work by the Kyoto artist Kako Katsumi (see photo below) is deep even though he's only in his 30's. I like his work a lot and want to support him.

M: What is the criterion of your selections?

RY: First is to trust one's own senses. I feel that the Japanese tend to follow brand names, but I choose what I want to use.

M: Now, after all, you still like yakishime basically?

RY: No, that was at first. Now, I like many things, Shino, Karatsu, and many different glazed wares. I think Mikami's black glaze is refined and profound. (See Guidebook for details on dozens of styles.)

M: Mikami-san, you brought all your own work? (see sixth photo from top of page)

MR: Yes. Black glazed pieces are my recent works.

KK: There is no other Japanese contemporary potter who makes better black than Mikami-san.

RY: Black yakimono is quite difficult. Mikami's black is fascinating.

MR: Well, it is just that I am interested in black. However, black is easily affected by other materials, and firing it in a wood-fired kiln is especially difficult.

M: Do you mean that it is not easy to get the black you want?

MR: Black has no color. In other words, there are uncountable kinds of black colors. There are blacks that are created from the thickness of glazes, from the oxidization in a kiln, or from the carbonization of a kiln. It's also affected by humidity and is influenced by how the kiln cools. It's quite interesting.

M: You've created many different types of work.

MR: Yes, I've made many styles.

M: What led you to making ceramics in the first place?

MR: I wanted to make vessels for sake. Before that, I was interested in oil painting and sculpture. I just like creating something. In my generation, we are Americanized on the surface. We know well about European and American art, but not about Japanese art. Therefore, I studied hard about beautiful Japanese things and came across yakimono. I had not payed much attention to where I stood. It's always darkest just beneath the lighthouse.

RY: I wholeheartedly agree. If young Japanese don't appreciate their roots it will certainly affect their identity. Guinomi like this may be considered luxury goods. But, if people stop buying guinomi, even ones that cost only 1000 yen, that will be a problem. The most important point is to use what "speaks to your senses," to use what you like. It's useless to have only knowledge. Pottery pieces have to be held and used. Something you use reflects your mind and heart. America is for sure a great country, but this "deep" Japanese culture is something very special.

M: I feel somehow embarrassed when Yellin-san says this. Well, Kuroda-san, could you show us what you brought here today?

KK: I brought pieces from my gallery, so I'm sorry that we can't use them.

This is a Ki-seto guinomi by Hara Kenji (see two photos up). I've known him for a long time. He's a taciturn person.

MR: It's a real neat lip, a fine piece.

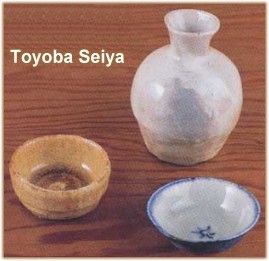

KK: These are a tokkuri and a guinomi by Toyoba Seiya (see photo earlier in story). If anything, Hara-san is more like Kato Tokuro, while Toyoba is more like Arakawa Toyozo.

RY: The lip reminds me of Arakawa Toyozo. It must be really good to use.

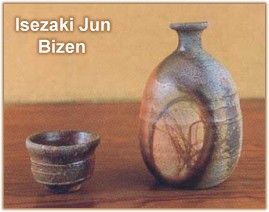

KK: Then we have a Bizen tokkuri and guinomi by Isezaki Jun (p.22).

M: It's generally said, "Tokkuri should come from Bizen, and guinomi from Karatsu." When did people begin saying that?

KK: Generally old Bizen (Ko-bizen) was made as a large tokkuri. Therefore, there are few good-sized ones (meaning good for one person). The other kinds are an abura (oil) tokkuri. We believe that the culture of chanoyu (tea ceremony), and especially of the kaiseki meal, became established after the Bunka-Bunsei period (1804-1830). This can be proven from historical documents of that period that mention kaiseki vessels. Originally, Bizen tokkuri was not made for use at the tea ceremony, but for everyday life. The same can be said about Karatsu guinomi. Tea masters found the beauty of everyday-use vessels and used them as charged tokkuri or guinomi at the tea ceremony. In those days, the tea ceremony was held only among daimyo (feudal lords) and wealthy merchants. The vessels and goods for the ceremony were kept stored in their warehouses and were not open to the public. By the Meiji Period (1868-1912), ordinary people had the chance to see tea-ceremony utensils -- those that belonged to feudal lords and wealthy merchants, those that were tendered or sold at auctions by Bijutsu Clubs (Art Clubs). People from financial circles, like Masuda Donnou, had successfully acquired such pieces with high bids. There are documents that describe their tea ceremonies in detail. I assume that as people began boasting about their Ko-Bizen tokkuri and Ko-Karatsu guinomi at the parties, those pieces became valued even more, and thus prices went up.

M: In relation to this, Bizen tokkuri have been talked about often since the Momoyama Period (1582-1598), right?

KK: That's right.

M: What about Karatsu guinomi?

KK: Regarding Ko-Karatsu guinomi, there are some theories. One is that they were made as trial pieces by Korean potters to demonstrate how to throw and fire for the Japanese, and the other theory is that they were made as vessels for delicacies rather than for use as guinomi. Originally, they were probably the type of vessels brought out for everyday use.

M: Is this tokkuri by Isezaki Jun (see above) a regular-sized Bizen tokkuri?

KK: This is rather big. However, please look at the keshiki (landscape); hidasuki, goma, "melon skin," all the highlights are there.

MR: It's a "melon skin," no doubt. Interesting.

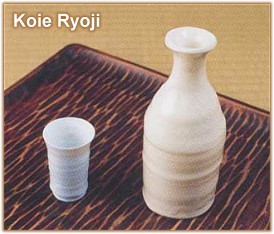

KK: I also brought some guinomi and tokkuri made by Koie Ryoji when he was in England (see above photo).

RY: This Guinomi looks almost like a liqueur glass. I can't sip from it because the lip of the guinomi would hit my nose. (laughs) The color of this would fit whisky as well. Koie-san himself likes to drink, so his shuki is wonderful, I think. He's a very special artist.

KK: Lastly, I brought celadon pieces by Kawase Shinobu.

RY: They're also good. Kawase-san likes to drink too.

KK: Celadon pieces are difficult to make in terms of the design because the glaze is very thick. His pieces are beautifully shaped with a thick glaze, amazing.

MR: I don't work with porcelain; therefore, I am attracted to a piece like this. I would like to drink using this tokkuri.

M: This tokkuri looks as if it would hold a lot of sake. Moreover, the shape is an exact pentagon.

KK: This is a perfect celadon piece without crackles.

MR: Wow, that's right. There are no crackles in it. This must have been very difficult to make.

M: Do crackles appear that easily?

MR: Yes, as soon as a work comes out of the kiln.

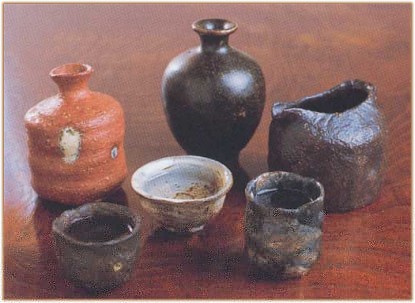

From right to left:

UEDA Tsuneji "Nerikomi Guinomi"

KAKO Katsumi "Haiyu Guinomi"

SAKAI Kobu "Shino Guinomi"

John DIX "Guinomi"

From the collection of Robert Yellin

THE PLEASURES OF COLLECTING SHUKI

M: You like sake, so does your yakimono collection consist mainly of shuki?

RY: Yes. Most Japanese houses are small and shuki don't take up too much space. They are also pretty easy to carry. I have an American friend living in Kamakura who is a sake critic. He's published three books on sake and we give seminars from time to time. I bring about 30 guinomi to each seminar. In addition, we can enjoy a variety of shuki styles. For instance, for Bizen, we can collect different keshiki on works, such as kase-goma (dry goma), tobi-goma (flying goma), and hidasuki. (See Guidebook for various Japanese glazes and keshiki).

M: In short, shuki is a miniature world of the whole yakimono world.

RY: Yes. When you look at 40 guinomi at once, each is very different from the other. Firing, kodai (foot), every part of it has it own character. In terms of chawan, kodai is an important part to look at, and the same can be said of a guinomi's kodai. You can feel the heart of a potter there. Kodai provides a lot of clues.

MR: Yellin-san, what you said is so true. Kodai is after all where a potter leaves all his message.

M: Westerners tend to have big hands. Is Japanese guinomi too small for you?

RY: Not at all. Some feel big even if they are small in actual size. For example, guinomi made by Furutani Michio feels big to me. Before Kaneshige Michiaki passed away, I bought his rather large guinomi. So I asked, "This guinomi is quite big, is it alright to use as a guinomi?" He replied, "Robert, you don't have to fill it up." (This was my first lesson in "ma" or "space.")

KK: One should pour just the amount that's right for them. It's not tasty when it's overflowing.

RY: You have to enjoy the empty space. Atmosphere is important.

M: Our magazine is having a campaign for new subscribers and we'll be giving out sake cups (guinomi) made by Nakajima Masanori. They are quite popular. Guinomi are good guides to the world of yakimono, and guinomi make you want to start a collection.

RY: I'm making good use of guinomi as a guide as well. There are various kinds of shuki and many ceramic artists make them. They have a long history, and old ones are fabulous too. It might be possible to acquire yamahai from the Kamakura period. Yet, because I am alive now, I appreciate being able to get to know contemporary artists. This Mikami piece can begin its own history from my hands. It's mysterious and interesting to wonder how and where that history will flow.

M: Even when made by the same artist, the guinomi differ -- it is significant that they are different. No wonder why guinomi are relatively expensive.

RY: Well, I don't think they are expensive. They will remain after time passes. The heart of the artist remains. Think about it -- if you can enjoy drinking with the guinomi for the next 30 years, it is rather cheap.

M: Wow, you are really into it. So, when you acquire a shuki, do you think about whether or not you can enjoy it for the next 10 years or so?

RY: Yes. I don't really calculate though. (laughs) I try to choose what I won't get tired of.

KK: It depends on your feelings. Even if you use the same guinomi you used the day before, it looks (feels) different.

MR: Pieces must have a blank space, for the day's feeling. If an artist makes a piece for his life and fills it up with his message, there won't be a blank space for the days to come. When you make one, you have to leave some space for the user to fill in with the user's own feeling.

RY: It's not all about technique. If technique alone is used to make a guinomi, the user will easily get tired of using it.

M: I see. That is a phrase pregnant with meaning. Oh dear! We've finished the food and sake before we even noticed. It seems we've also reached the end of our discussion. I got intoxicated with good sake and shuki. Thank you all very much.

LEARN MORE

|